Shane Jones’ $3 billion Provincial Growth Fund has shone a light on regional economic development. But there are still a lot of misconceptions about what regional economic development is and what projects hope to achieve. This Top 5, originally posted on interest.co.nz, explores selected elements of what regional economic development practitioners think about.

1. Making a place great to live, work, and do business

Economic development is not a tool for cherry picking winners, rather it is about creating a space for entrepreneurialism to flourish. A core focus of many regional economic development strategies is supporting initiatives that make a place great to live, work and do business. If you get the basics right and tell the story well, then residents will want to stay and outsiders will want to move to your area. People are the building blocks of an economy, irrespective of whether they contribute productively as workers in existing enterprises or utilise their talents and capital to invest in businesses that employ others.

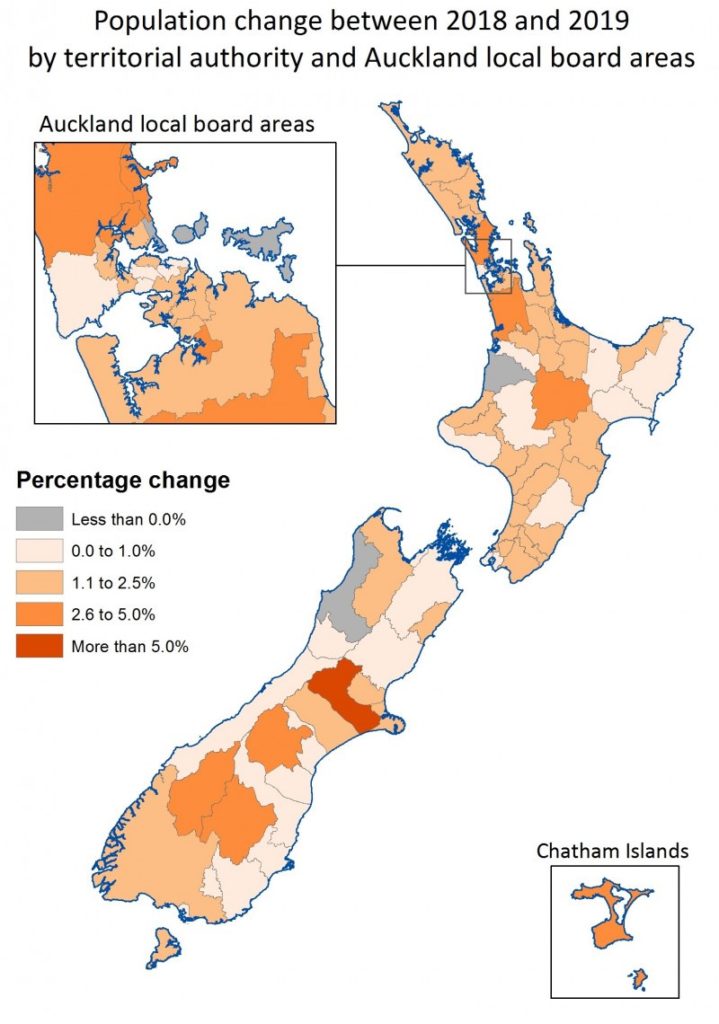

Statistics New Zealand subnational population estimates from the June 2019 year show which parts of New Zealand are most successfully attracting and retaining people.

“While both the North and South islands had overall growth similar to the national average of 1.6 percent, there were a range of growth rates across the territorial authority areas within each island. For example, in the South Island, the Selwyn district had a 5.3 percent increase with Buller district declining by 0.3 percent in the June year. In the North Island, Waikato district had a 2.8 percent increase, while Waitomo district had a 0.9 percent decrease in population over the same period.”

2. Economic Development is a long game

Quick wins in economic development are hard to find, and regions need to play the long game. Shane Jones and the Provincial Growth Fund (PGF) are learning things the hard way. Most of the PGF’s $3 billion has already been earmarked for projects, but very little of the money has actually been distributed and relatively few jobs have been created.

The reality is that there are long lag times between conceptualising an idea, planning for implementation and getting things operational. It’s harder to spend $3 billion and create jobs in a hurry than Jones had thought.

Some statistics from within the fund’s first two years:

“The latest job figures have been released, showing 1854 were employed in Provincial Growth Fund projects.

Of those, 616 were full-time, 637 were part-time and 601 had an “unknown” status.

The figures showed 520 jobs are in the tourism sector, 249 in roading, 142 in rail and 246 of the jobs are for those working on feasibility studies.

It was estimated that 10,000 jobs would be created overall from the fund.”

3. Economic gardening is just as important as starting new enterprise

Business attraction is a key focus of regional economic development. The rationale is that new businesses create jobs, which in turn support wellbeing in local communities. But I am often left wondering whether this focus makes sense in the real world.

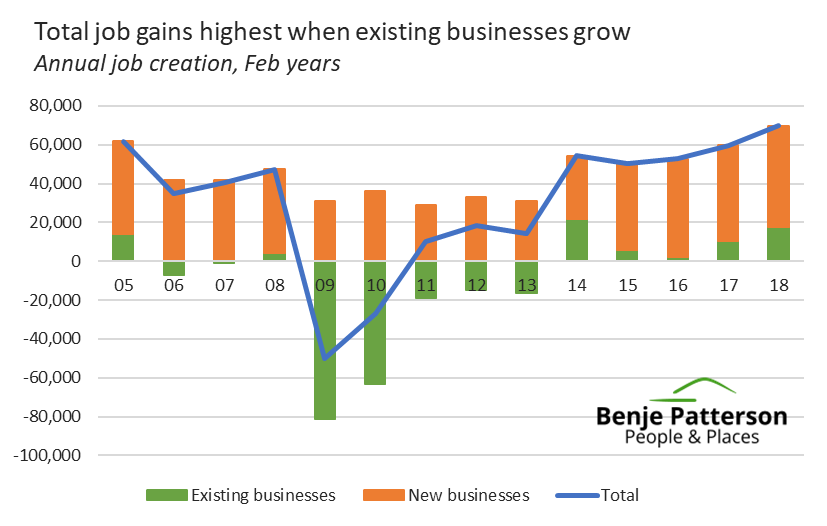

I decided to test whether new or existing businesses are the engine for jobs growth in regional New Zealand.

The answer to my investigation is that both economic development roles matter. New businesses generate a steady stream of jobs across all parts of the country, but these gains can be quickly eroded when existing businesses backpedal.

“Although startups are indeed an important part of the jobs growth engine and must be supported, excessive swings in the fortunes of existing business are the more detrimental factor during bad times.

Some natural pruning is warranted to weed out business models that are out-of-sync with longer-term trends in supply and demand, but there are some businesses that fail because they have insufficient resilience to weather short-term storms.

This need to build up resilience provides relevancy to the work that economic development practitioners do with existing enterprises to help them become more cost efficient, productive, competitive, and sustainably financed.”

4. The working world and what people choose to do is changing

Understanding how megatrends influence a region is a key consideration for economic development practitioners. For example, an increasing number of remote workers is a megatrend that is beginning to shape the working environment in many regions.

These people could choose to live anywhere in New Zealand (or even the world) and still earn their income remotely, but have chosen to live in a particular place for family or lifestyle reasons.

Economic development practitioners want to develop their understanding of these remote workers. Attracting such people to your area can bring higher incomes and diversification, while tapping into the skills, expertise and capital of remote workers could potentially lift productivity and lead to further job creation.

Although not the quite the same thing as remote work, Statistics New Zealand is expanding its ways of understanding what proportion of people have flexible working arrangements. The findings make for interesting reading:

“The industries with the highest proportion of ‘flexitime’ arrangements were rental, hiring, and real estate services; and professional, scientific, and technical services, where over 70 percent of employees had flexible work hours.

Those with flexible hours reported higher levels of satisfaction with both their job and their work-life balance than those without.

16 percent of employees had an arrangement with their employer allowing them to work from home but continue to be paid.

22 percent of parents to a dependent child had an arrangement with their employer to be paid for work done at home, compared with 14 percent of non-parents.”

5. Economic development needs to be inclusive

Economic development is not just about dollars and cents, people and the environment matter too. Sustainable development is the sweet spot that balances all three.

Economic development practitioners are learning that there can be synergies between what is good for people and the environment, as well as what is good for business. Happy people are more productive, while happy and healthy societies operate more cohesively and efficiently.

According to the World Economic Forum:

There is no inherent trade-off between promoting social inclusion and economic growth and competitiveness. It is possible to be pro-equity and pro-growth at the same time; not only is it impossible to improve everyone’s living standards without growing the economic pie, but policies that improve living standards and influence the way in which the pie is shared can also bolster growth. Several of the strongest performers in the Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index are good at ensuring that growth proceeds in a way that includes the many rather than the few.