Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is often misused as a headline measure of the wellbeing of people in New Zealand and around the globe, even though such conclusions go beyond what GDP was originally designed for.

Put simply, GDP is merely a measure of an economy’s capacity to produce and isn’t a good way of grading end outcomes for our society as a whole or how individuals are faring.

As a result, decision makers should refrain from an overreliance on this single summary statistic and instead always focus on a wider panel of indicators for monitoring their economy and making policy decisions.

This conclusion is particularly applicable in the New Zealand context, where a renewed focus on regional economic development has meant that significant emphasis is being put on understanding differences in economic wellbeing between our regions.

What is GDP anyway?

Before considering the need to monitor wellbeing in your region, let’s take a more detailed look at where GDP came from and what its limitations are.

The modern concept of GDP was a by-product of the Great Depression, when people wanted a yardstick for valuing how much an economy could produce.

Put in slightly more formal terms, GDP was designed to quantify the value added at each stage of production across all final goods and services produced within a geographical area over a fixed period of time (usually a quarter or a year).

Given that these final goods and services, that make up the production-based definition of GDP, can be sold or traded, GDP is often also thought of as an income flow that is able to fund consumption and investment.

It is from this logic that some people then make the heroic assumption that GDP can be used as a proxy of wellbeing in a region, presumably on the basis that a higher level of consumption indicates more people satisfying their lifestyle demands.

At face value, this logic may make sense, but if we back up a couple of steps, it’s not hard to unpick some shortcomings in this approach.

The limitations of GDP

There are many limitations of using GDP as a complete measure of understanding people’s wellbeing, but let’s take a quick look at a few of them.

The first key limitation of GDP is that it only measures market transactions. GDP does not include non-market transactions (like when you dogsit for your neighbour), and it does not count the benefit of leisure (because simple pleasures like enjoying relaxing in front of the fire are not a market transaction). In a similar vein, factors such as how content people are feeling and their physical state of health can also not be captured using market transactions.

Another limitation of GDP is that it only considers a one-time flow of activity over a fixed time period, and does not take a broader look at the underlying wealth and resources at an area’s disposal. Surely any assessment of how well off an area is must look at the land, capital, labour, and other accumulations of resources that can be used to generate future economic activity, support healthy lifestyles, and provide for the next generation.

GDP also does not distinguish between how the activity has been funded and where productive capacity is being targeted. This matters as failing to consider debt financing and what it is being used to produce, invest in, or consume is asking for trouble. If you have any doubt, consider all the money Greece borrowed for frivolous consumption and where that got them.

Also even if GDP goes up, that doesn’t mean everyone will benefit. The capital owners may be the ones that have benefited from growth, with very little flowing through into the back pockets of workers. A lack of awareness of this issue is what led to the Occupy Wall Street movement.

Finally, GDP is a highly conceptual measure that is prone to revisions as methodologies are improved or new types of input data become available. As a result, it is wise to also consider variables that can be more tangible assessed against outcomes that are less frequently revised.

Considering wellbeing in New Zealand’s regions

Despite the flaws identified above, GDP is still asked to inform policy decisions on a range of issues.

The appeal of GDP for policy makers is its simplicity as a summary statistic that can instantly give people a feel for how an economy is going.

Using GDP as one performance metric is not a problem persay, but things do get pretty dicey when it is used as a key indicator in more complex policy decisions, involving wellbeing differences between people and regions.

Instead policy makers should consider a range of indicators that have been broken down into a fine level of geographical disaggregation and are updateable. In this way, regions can be sure that they can benchmark themselves against places facing similar challenges and monitor improvements through time.

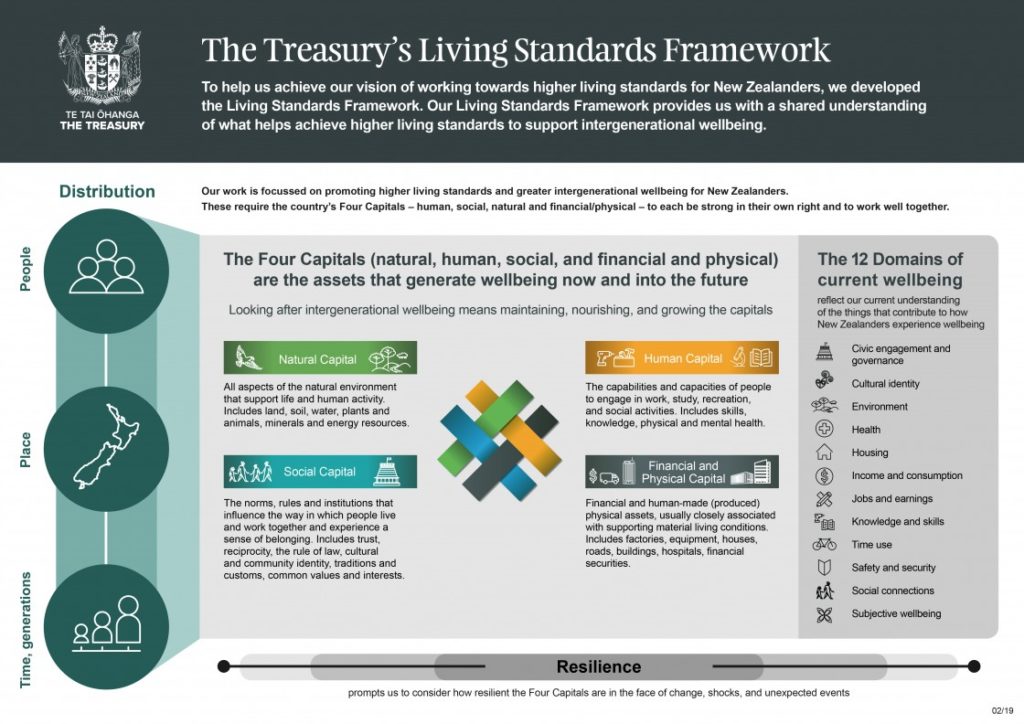

A good starting point for trying to understand the types of data you should consider for monitoring wellbeing is the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework. The Framework outlines 12 domains of current wellbeing and four capitals (natural, human, social, and financial and physical) that can help underpin future wellbeing.

Regional decision-makers should stop and take note of the Treasury’s work.

The Treasury’s framework ultimately guided the allocation of central government funding in Budget 2019. Wellbeing ideals are also embedded in the objectives in the Provincial Growth Fund. Furthermore, measuring success based on the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework allows local authorities to meet their statutory requirement under the Local Government Act to factor social, economic, environmental and cultural wellbeing into decision-making processes.

Summary

- Regional economic development requires appropriate regional economic data for monitoring purposes and making evidence-based decisions

- GDP has limitations and should only be used for getting a headline summary of economic activity

- To understand wellbeing and performance more generally a broader panel of indicators beyond a narrow GDP focus must be used

- All indicators must be able to be updated and benchmarked against peers in other regions

- The Treasury’s Living Standards framework is a good starting point for understanding ways of looking at wellbeing

- Consistency with the Treasury’s work allows your organisation to sing from the same song sheet when accessing central government funding and helps meet statutory requirements to consider wellbeing under the Local Government Act.

A previous version of this article also appeared on Interest.co.nz.